Modeling variation in abundance using capture-recapture data

Richard Chandler

Feb 24, 2019

Source:vignettes/cap-recap.Rmd

cap-recap.RmdAbstract

The “un” in unmarked is somewhat misleading because the

package can be used to analyze data from marked animals. The three most

common sampling methods that produce suitable data are removal sampling,

double observer sampling, and capture-recapture methods. This document

focuses on the analysis of capture-recapture data using a class of

models known as multinomial

-mixture

models (Royle 2004, Dorazio et al. 2005),

which assume that capture-recapture data have been collected at a

collection of sample locations (“sites”). Capture-recapture models can

be fitted with constant parameters

(),

time-specific parameters

(),

and behavioral responses

().

In addition, spatial variation in abundance and capture probability can

also be modeled using covariates. unmarked has two

functions for fitting capture-recapture models:

multinomPois and gmultmix. Both allow for

user-defined functions to describe the capture process, and the latter

allows for modeling of temporary emigration when data have been

collected using the so-called robust design (Kendall et al. 1997, Chandler et al. 2011).

Introduction

In traditional capture-recapture models, individuals are captured at a site during the course of sampling occasions. The encounter history for each individual is used as information about capture probability such that the total population size can be regarded as the size parameter of a binomial distribution, .

Although traditional capture-recapture models are useful for estimating population size when , they do not allow one to model variation in abundance, which is a central focus of much ecological research. Royle (2004) and Dorazio et al. (2005) developed a framework for modeling variation in both abundance and capture probability when capture-recapture data are collected at a set of sites. Site-specific abundance () is regarded as latent variable following a discrete distribution such as the Poisson or negative binomial. The encounter histories are then tabulated at each site so that they can be regarded as an outcome of a multinomial distribution with cell probabilities $\bf \pi$ determined by a protocol-specific function of capture probability. Assuming a Poisson distribution, the model can be written as $$ \begin{gather} N_i \sim \mbox{Poisson}(\lambda) \nonumber \\ {\bf y_i}|N_i \sim \mbox{Multinomial}(N_i, \pi(p)) \label{mod} \end{gather} $$ In the above, is the expected number of individuals at each site. ${\bf y_i}$ is a vector containing the number of individuals with encounter history at site . The number of observable encounter histories depends on the sampling protocol. For a capture-recapture study with 2 occasions, there are 3 possible encounter histories . In Equation 1, is a function that that converts capture probability to multinomial cell probabilities, , the proportion of individuals expected to have capture history . For example, the cell probabilities corresponding to the capture histories listed above are

$$ {\bf \pi}(p) = \{ p^2, p(1-p), (1-p)p \}. $$

The probability of not capturing an individual in this case () is .

Spatial variation in abundance can be modeled using covariates with a log-link function where is some site-specific covariate such as habitat type or elevation. Multiple covariates can be considered and a more general form of the above can be written as $\log(\lambda_i) = {\bf X}_i' \bf \beta$ where ${\bf X}$ is a design matrix and ${\bf \beta}$ is a vector of coefficients, possibly including an intercept. Capture probability can be modeled using the logit-link in much the same way where is some covariate specific to the site and capture occasion. When is assumed to be constant, the model is often referred to as model . Alternatively, may be occasion-specific (model ) or may be influenced by animal behavior (model ). Otis et al. (1978) and Williams et al. (2002) are comprehensive references.

Data

As previously mentioned, the data required by unmarked

are an

matrix in which each row is the vector of tabulated encounter histories

for animals captured at some site. Capture-recapture data, however, is

typically recorded in the format shown in Table 1.

| Animal ID | Site | Capture history |

|---|---|---|

| GB | A | 101 |

| YR | A | 101 |

| RO | A | 111 |

| PP | A | 100 |

| GY | B | 100 |

| PR | B | 010 |

In the absence of individual covariates, the data in Table 1 can be converted to the requisite format as shown in Table 2. Notice that no captures were made in sites C and D. It is important that such sites are retained in the analysis in order to make inference about spatial variation in abundance.

| Site | 100 | 010 | 001 | 110 | 011 | 101 | 111 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| B | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Closed Population Models

Models , , and models with covariates of .

In this example we will analyze point count data collected on alder flycatchers (Empidonax alnorum) by Chandler et al. (2009). Point count data such as these are collected on unmarked animals, but one can apply capture-recapture models because it is possible to keep track of individual birds during a short period of time (Alldredge et al. 2007). That is, we can pretend like birds are marked by noting which time intervals they are detected in during a short survey. The alder flycatcher data were collected using fixed-area 15-minute point counts, which were divided into 3 5-minute intervals. Each point was surveyed 3 times during 2005. The following command imports the capture histories for 50 individuals detected in 2005 at 49 point count locations.

alfl <- read.csv(system.file("csv", "alfl.csv", package="unmarked"))

head(alfl, 5)## id survey interval1 interval2 interval3

## 1 crick1_05 1 1 1 1

## 2 crick1_05 3 1 0 1

## 3 his1_05 1 0 1 1

## 4 his1_05 1 1 1 1

## 5 his1_05 2 0 1 1We see 5 rows of data representing the encounter histories for 5 birds detected at 2 points during 3 survey occasions. From these 5 birds, it appears as though detection probability is high since each bird was detected during at least 2 of the three time intervals.

Associated with the bird data are site- and visit-specific covariates for each of the 49 sites. We can import these data using the following command:

alfl.covs <- read.csv(system.file("csv", "alflCovs.csv",

package="unmarked"), row.names=1)

head(alfl.covs)## struct woody time.1 time.2 time.3 date.1 date.2 date.3

## crick1_05 5.45 0.30 8.68 8.73 5.72 6 25 34

## his1_05 4.75 0.05 9.43 7.40 7.58 20 32 54

## hisw1_05 14.70 0.35 8.25 6.70 7.62 20 32 47

## hisw2_05 5.05 0.30 7.77 6.23 7.17 20 32 47

## kenc1_05 4.15 0.10 9.57 9.55 5.73 8 27 36

## kenc2_05 9.75 0.40 9.10 9.12 9.12 8 27 36Each row of this data.frame corresponds to a point count

location. The variable struct is a measure of vegetation

structure, and woody is the percent cover of woody

vegetation at each of the 50-m radius plots. Time of day and date were

measured for each of the three visits.

To format the data for unmarked, we need to tabulate the

encounter histories for each site. Before doing so, let’s first put our

capture histories in a single column. Let’s also be explicit about the

levels of our factors for both the newly created

captureHistory column and the point id column.

alfl$captureHistory <- paste(alfl$interval1, alfl$interval2, alfl$interval3, sep="")

alfl$captureHistory <- factor(alfl$captureHistory,

levels=c("001", "010", "011", "100", "101", "110", "111"))

## Don't do this:

#levels(alfl$id) <- rownames(alfl.covs)

alfl$id <- factor(alfl$id, levels=rownames(alfl.covs))Specifying the levels of captureHistory ensures that

when we tabulate the encounter histories, we will include zeros for

histories that were not observed. Similarly, setting the levels of

alfl$id tells R that there were some sites

where no ALFL were detected. This way, when we tabulate the data, we get

a frequency for each site, not just the ones with >1 detection. Here

are the commands to extract data from the first primary period and to

tabulate the encounter histories.

alfl.v1 <- alfl[alfl$survey==1,]

alfl.H1 <- table(alfl.v1$id, alfl.v1$captureHistory)

head(alfl.H1, 5)##

## 001 010 011 100 101 110 111

## crick1_05 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

## his1_05 0 0 1 0 0 0 1

## hisw1_05 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

## hisw2_05 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

## kenc1_05 0 0 0 0 0 0 0The object alfl.H1 contains the tabulated capture

histories for each site. This is the format required by

unmarked. The data from the first 5 sites suggest that

detection probability was high since the most common encounter history

was 111.

Now we are almost ready to create our unmarkedFrame and

begin fitting models. We will fit our first series of models using the

multinomPois function, which requires data formated using

the unmarkedFrameMPois function. This constructor function

has an argument , which currently can be set to "removal"

or "double", corresponding to removal sampling data and

double observer sampling respectively. In doing so, the function

automatically creates the function to convert

to ${\bf \pi}$. If type is

missing, however, the user needs to specify a function to convert

detection probability to multinomial cell probabilities. In the future,

we may add an option to automatically handle standard capture-recapture

data too, but here we show how to supply it using a user-defined

piFun, which allows flexibility in converting detection

probability to multinomial cell probabilities $\bf \pi$. The piFun must take a

matrix of detection probabilities with

columns (3 in this case), and convert them to a matrix of multinomial

cell probabilities with

columns. Each column corresponds to the probability of observing the

encounter history

.

Here is a piFun to compute the multinomial cell

probabilities when there were 3 sampling occasions. This function allows

us to fit models

,

,

or models with covariates of

.

crPiFun <- function(p) {

p1 <- p[,1]

p2 <- p[,2]

p3 <- p[,3]

cbind("001" = (1-p1) * (1-p2) * p3,

"010" = (1-p1) * p2 * (1-p3),

"011" = (1-p1) * p2 * p3,

"100" = p1 * (1-p2) * (1-p3),

"101" = p1 * (1-p2) * p3,

"110" = p1 * p2 * (1-p3),

"111" = p1 * p2 * p3)

}To demonstrate how this works, imagine that we surveyed 2 sites and detection probability was constant () among sites and survey occasions. The function converts these capture probabilities to multinomial cell probabilities. Note that these cell probabilities will sum to <1 if capture probability is less than 1 over the 3 occasions.

p <- matrix(0.4, 2, 3)

crPiFun(p)## 001 010 011 100 101 110 111

## [1,] 0.144 0.144 0.096 0.144 0.096 0.096 0.064

## [2,] 0.144 0.144 0.096 0.144 0.096 0.096 0.064

rowSums(crPiFun(p))## [1] 0.784 0.784When providing a user-defined , we also need to provide information

about how to handle missing values. That is, if we have a missing value

in a covariate, we need to know which values of ${\bf y}$ are affected. In

unmarked, this can be done by supplying a mapping-matrix to

the obsToY argument in the unmarkedFrameMPois

function. obsToY needs to be a matrix of zeros and ones

with the number of rows equal to the number of columns for some obsCov,

and the number columns equal to the number of columns in ${\bf y}$. If obsToY[j,k]=1,

then a missing value in obsCov[i,j] translates to a missing

value in y[i,k]. For the capture-recapture data considered

here, we can set all elements of obsToY to 1.

o2y <- matrix(1, 3, 7)We are now ready to create the unmarkedFrame. In order

to fit model

,

we need a covariate that references the time interval , which we call

intervalMat below. We also provide a couple of

site-specific covariates: the percent cover of woody vegetation and

vegetation structure.

library(unmarked)

intervalMat <- matrix(c('1','2','3'), 50, 3, byrow=TRUE)

class(alfl.H1) <- "matrix"

umf.cr1 <- unmarkedFrameMPois(y=alfl.H1,

siteCovs=alfl.covs[,c("woody", "struct", "time.1", "date.1")],

obsCovs=list(interval=intervalMat),

obsToY=o2y, piFun="crPiFun")## Warning: obsCovs contains characters. Converting them to factors.Writing a piFun and creating the obsToY

object are the hardest parts of a capture-recapture analysis in

unmarked. Again, this is done automatically for removal

models and double observer models, and we may add an option to do this

automatically for capture-recapture data too, but hopefully the

flexibility allowed by specifying user-defined functions is evident.

Now that we have our data formatted we can fit some models. The following correspond to model , model , and a model with a continuous covariate effect on .

M0 <- multinomPois(~1 ~1, umf.cr1, engine="R")

Mt <- multinomPois(~interval-1 ~1, umf.cr1, engine="R")

Mx <- multinomPois(~time.1 ~1, umf.cr1, engine="R")The first two models can be fit in other software programs. What is

unique about unmarked is that we can also model variation

in abundance and detection probability among sites. The following model

treats abundance as a function of the percent cover of woody

vegetation.

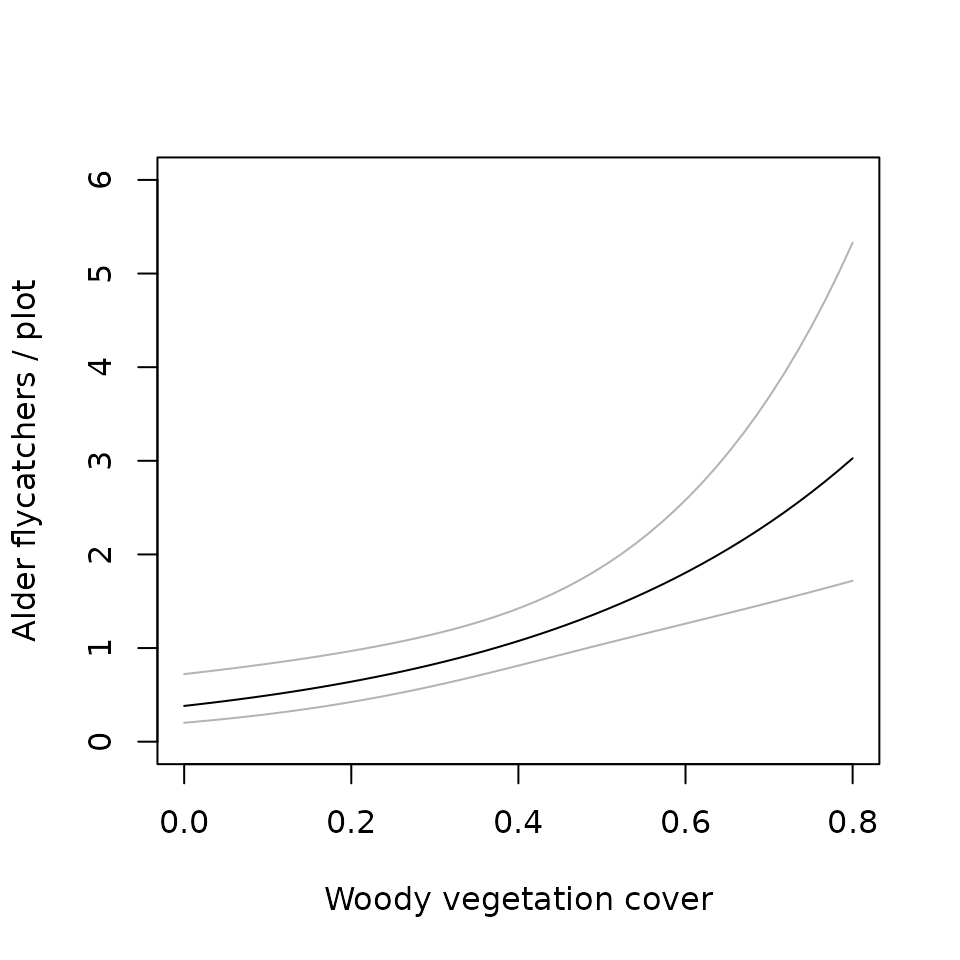

(M0.woody <- multinomPois(~1 ~woody, umf.cr1, engine="R"))##

## Call:

## multinomPois(formula = ~1 ~ woody, data = umf.cr1, engine = "R")

##

## Abundance (log-scale):

## Estimate SE z P(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -0.962 0.325 -2.96 0.003059

## woody 2.587 0.680 3.80 0.000143

##

## Detection (logit-scale):

## Estimate SE z P(>|z|)

## 1.43 0.216 6.63 3.42e-11

##

## AIC: 245.9301

## Number of sites: 50

nd <- data.frame(woody=seq(0, 0.8, length=50))

E.abundance <- predict(M0.woody, type="state", newdata=nd, appendData=TRUE)

plot(Predicted ~ woody, E.abundance, type="l", ylim=c(0, 6),

ylab="Alder flycatchers / plot", xlab="Woody vegetation cover")

lines(lower ~ woody, E.abundance, col=gray(0.7))

lines(upper ~ woody, E.abundance, col=gray(0.7))

What about detection probability? Since there was no evidence of

variation in

,

we can run predict on the model with

type = 'det' in order to back-transform the logit-scale

estimate and obtain

.

We show just the first row of the output since all sites/occasions have

identical .

predict(M0.woody, type='det')[1,]## Predicted SE lower upper

## 1 0.807521 0.03363115 0.7330001 0.8650715As suggested by the raw data, detection probability was very high.

The corresponding multinomial cell probabilities can be computed by

plugging this estimate of detection probability into our

piFun. This getP function makes this easy.

## 001 010 011 100 101 110 111

## 0.03 0.03 0.13 0.03 0.13 0.13 0.53Note that the encounter probability most likely to be observed was 111. In fact was so high that the probability of not detecting an alder flycatcher was essentially zero, .

Modeling behavioral responses, Model

An animal’s behavior might change after being captured. Both trap avoidance and trap attraction are frequently observed in a variety of taxa. A simple model of these two behaviors is known as model (Otis et al. 1978). The model assumes that newly-captured individuals are captured with probability and then are subsequently recaptured with probability . If , then animals exhibit trap avoidance. In some cases, such as when traps are baited, we might observed in which case the animals are said to be “trap-happy”.

To fit model

in unmarked, we need to create a new piFun and

we need to provide an occasion-specific covariate (obsCov)

that distinguishes the two capture probabilities,

and

.

The simplest possible approach is the following

crPiFun.Mb <- function(p) { # p should have 3 columns

pNaive <- p[,1]

pWise <- p[,3]

cbind("001" = (1-pNaive) * (1-pNaive) * pNaive,

"010" = (1-pNaive) * pNaive * (1-pWise),

"011" = (1-pNaive) * pNaive * pWise,

"100" = pNaive * (1-pWise) * (1-pWise),

"101" = pNaive * (1-pWise) * pWise,

"110" = pNaive * pWise * (1-pWise),

"111" = pNaive * pWise * pWise)

}This function crPiFun.Mb allows capture probability to

be modeled as

where

is simply a dummy variable. Thus, when no site-specific covariates

()

are included,

is either

or

.

The following code constructs a new unmarkedFrame and fits

model

to the alder flycatcher data.

behavior <- matrix(c('Naive','Naive','Wise'), 50, 3, byrow=TRUE)

umf.cr1Mb <- unmarkedFrameMPois(y=alfl.H1,

siteCovs=alfl.covs[,c("woody", "struct", "time.1")],

obsCovs=list(behavior=behavior),

obsToY=o2y, piFun="crPiFun.Mb")## Warning: obsCovs contains characters. Converting them to factors.

M0 <- multinomPois(~1 ~1, umf.cr1Mb, engine="R")

(Mb <- multinomPois(~behavior-1 ~1, umf.cr1Mb, engine="R"))##

## Call:

## multinomPois(formula = ~behavior - 1 ~ 1, data = umf.cr1Mb, engine = "R")

##

## Abundance (log-scale):

## Estimate SE z P(>|z|)

## 0.00955 0.142 0.0674 0.946

##

## Detection (logit-scale):

## Estimate SE z P(>|z|)

## behaviorNaive 1.31 0.356 3.69 2.25e-04

## behaviorWise 1.50 0.276 5.44 5.27e-08

##

## AIC: 260.0599

## Number of sites: 50AIC gives us no reason to favor model over model . This is perhaps not too surprising given that the alder flycatchers were not actually captured. Here is a command to compute 95% confidence intervals for the two detection probabilities.

## Profiling parameter 1 of 2 ... done.

## Profiling parameter 2 of 2 ... done.## 0.025 0.975

## p(behaviorNaive) 0.6490219 0.8846530

## p(behaviorWise) 0.7290778 0.8890318Caution, Warning, Danger

The function crPiFun.Mb is not generic and could easily

be abused. For example, you would get bogus results if you tried to use

this function to fit model

,

or if you incorrectly formatted the behavior covariate.

Thus, extreme caution is advised when writing user-defined

piFuns.

There are also a few limitations regarding user-defined

piFuns. First, they can only take a single argument

p, which must be the

matrix of detection probabilities. This makes it cumbersome to fit

models such as model

as described below. It also makes it impossible to fit models such as

model

.

It would be better if piFuns could accept multiple

arguments, but this would require some modifications to

multinomPois and gmultmix, which we may do in

the future.

Individual Heterogeneity in Capture Probability, Model

The capture-recapture models covered thus far assume that variation

in capture probability can be explained by site-specific covariates,

time, or behavior. Currently, unmarked can not fit

so-called individual covariate models, in which heterogeneity in

is attributable to animal-specific covariates. However, one could

partition the data into strata and analyze the strata separately. For

example, sex-specific differences could be studied by dividing the data

on males and females into 2 subsets.

Although individual covariate models cannot be considered, it is

possible to fit model

,

which assumes random variation in capture probability among individuals.

Here is a piFun, based on code by Andy Royle. It assumes a

logit-normal distribution for the random effects

These random effects are integrated out

of the likelihood to obtain the marginal probability of capture.

MhPiFun <- function(p) {

mu <- qlogis(p[,1]) # logit(p)

sig <- exp(qlogis(p[1,2]))

J <- ncol(p)

M <- nrow(p)

il <- matrix(NA, nrow=M, ncol=7)

dimnames(il) <- list(NULL, c("001","010","011","100","101","110","111"))

for(i in 1:M) {

il[i,1] <- integrate( function(x) {

(1-plogis(mu[i]+x))*(1-plogis(mu[i]+x))*plogis(mu[i]+x)*dnorm(x,0,sig)

}, lower=-Inf, upper=Inf, stop.on.error=FALSE)$value

il[i,2] <- integrate( function(x) {

(1-plogis(mu[i]+x))*plogis(mu[i]+x)*(1-plogis(mu[i]+x))*dnorm(x,0,sig)

}, lower=-Inf, upper=Inf, stop.on.error=FALSE)$value

il[i,3] <- integrate( function(x) {

(1-plogis(mu[i]+x))*plogis(mu[i]+x)*plogis(mu[i]+x)*dnorm(x,0,sig)

}, lower=-Inf, upper=Inf, stop.on.error=FALSE)$value

il[i,4] <- integrate( function(x) {

plogis(mu[i]+x)*(1-plogis(mu[i]+x))*(1-plogis(mu[i]+x))*dnorm(x,0,sig)

}, lower=-Inf, upper=Inf, stop.on.error=FALSE)$value

il[i,5] <- integrate( function(x) {

plogis(mu[i]+x)*(1-plogis(mu[i]+x))*plogis(mu[i]+x)*dnorm(x,0,sig)

}, lower=-Inf, upper=Inf, stop.on.error=FALSE)$value

il[i,6] <- integrate( function(x) {

plogis(mu[i]+x)*plogis(mu[i]+x)*(1-plogis(mu[i]+x))*dnorm(x,0,sig)

}, lower=-Inf, upper=Inf, stop.on.error=FALSE)$value

il[i,7] <- integrate( function(x) {

plogis(mu[i]+x)*plogis(mu[i]+x)*plogis(mu[i]+x)*dnorm(x,0,sig)

}, lower=-Inf, upper=Inf, stop.on.error=FALSE)$value

}

return(il)

}This function does not allow for temporal variation in capture

probability because we are using the second column of p as

,

the parameter governing the variance of the random effects. Once again,

this is somewhat clumsy and it would be better to allow

piFun to accept additional arguments, which could be

controlled from multinomPois using an additional

formula. Such features may be added eventually.

Having defined our new piFun, we can fit the model as

follows

parID <- matrix(c('p','sig','sig'), 50, 3, byrow=TRUE)

umf.cr2 <- unmarkedFrameMPois(y=alfl.H1,

siteCovs=alfl.covs[,c("woody", "struct", "time.1")],

obsCovs=list(parID=parID),

obsToY=o2y, piFun="MhPiFun")

multinomPois(~parID-1 ~woody, umf.cr2)## Call:

## multinomPois(formula = ~parID - 1 ~ woody, data = umf.cr2)

##

## Abundance:

## Estimate SE z P(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -0.84 0.363 -2.31 0.02078

## woody 2.59 0.680 3.81 0.00014

##

## Detection:

## Estimate SE z P(>|z|)

## parIDp 1.637 0.645 2.54 0.0112

## parIDsig 0.841 0.622 1.35 0.1762

##

## AIC: 242.3731The estimate of is high, indicating the existence of substantial heterogeneity in detection probability. However, one should be aware of the concerns about raised by Link (2003) who demonstrated that population size is not an identifiable parameter among various classes of models assumed for the random effects. For example, we might use a beta distribution rather than a logit-normal distribution, and obtain very different estimates of abundance. Link (2003) demonstrated that conventional methods such as AIC cannot be used to discriminate among these models.

Distance-related heterogeneity

Another source of individual heterogeneity in capture probability

arises from the distance between animal activity centers and sample

locations. Traditional capture-recapture models ignore this important

source of variation in capture probability, but recently developed

spatial capture-recapture (SCR) models overcome this limitation (Efford 2004, Royle and Dorazio 2008, Royle and Young

2008). Distance-related heterogeneity in detection probability

was probably not an important concern in the alder flycatcher dataset

because the plots were very small (0.785 ha) and only singing birds were

included in the analysis. If it were a concern, we could of course

collect distance data and use the gdistsamp function to fit

a distance sampling model. In other contexts, such as when using arrays

of live traps, distance sampling is not an option and SCR models offer

numerous advantages over traditional capture-recapture models.

Modeling Temporary Emigration

In the previous analysis we used data from the first visit only. Chandler et al. (2011) proposed a model that allows us to make use of the entire alder flycatcher dataset. The model is similar to the temporary emigration model of Kendall et al. (1997) except that we are interested in modeling variation in abundance among sites.

The model assumes that no births or deaths occur during the study period, but animals may move on and off the plots between sampling occasions. This type of movement is referred to as temporary emigration. To account for it, define to be the super-population size, the total number of individuals that use site during the study period. Assume that we visit each site on primary periods and define to be the subset of exposed to sampling during primary period . We now collect capture-recapture data at each site during each primary period, and obtain the data $\bf y_{it}$. The model can be written as $$ \begin{gather} M_i \sim \mbox{Poisson}(\lambda) \nonumber \\ N_{it}|M_i \sim \mbox{Binomial}(M_i, \phi) \nonumber \\ {\bf y_{it}}|N_{it} \sim \mbox{Multinomial}(N_{it}, \pi(p)) \label{mod:te} \end{gather} $$ where is the probability of being available for capture. This can be modeled as a function of covariates using the logit-link.

The data structure for the robust design is more complex than before,

but it is easy to create in R. We can once again use the

table function - but this time, we create a

three-dimensional table rather than a two-dimensional one. We also need

to expand the obsToY mapping matrix so that it has a block

diagonal structure. This isn’t so intuitive, but the commands below are

generic and can be applied to other capture-recapture designs.

alfl.H <- table(alfl$id, alfl$captureHistory, alfl$survey)

alfl.Hmat <- cbind(alfl.H[,,1], alfl.H[,,2], alfl.H[,,3])

nVisits <- 3

o2yGMM <- kronecker(diag(nVisits), o2y)

umf.cr <- unmarkedFrameGMM(y=alfl.Hmat,

siteCovs=alfl.covs[,c("woody", "struct")],

yearlySiteCovs=list(date=alfl.covs[,3:5], time=alfl.covs[,6:8]),

obsCovs=list(interval=cbind(intervalMat,intervalMat,intervalMat)),

obsToY=o2yGMM, piFun="crPiFun", numPrimary=nVisits)## Warning: obsCovs contains characters. Converting them to factors.Notice that we have 3 types of covariates now. The site-specific

covariates are the same as before. Now, however, the observation

covariates must match the dimensions of the ${\bf y}$ matrix. We can also have a class of

covariates that vary among primary periods but not within primary

periods. These are called yearlySiteCovs, which is a

misleading name. It is a carry-over from other “open population” models

in unmarked, but it should be remembered that these models

are most suitable for data from a single year, since we assume no births

or mortalities.

We can fit the model using the gmultmix function, which

has a slightly different set of arguments. Rather than a single formula,

the function takes 3 formulas for abundance covariates, availability

covariates, and detection covariates in that order.

(fm1 <- gmultmix(~woody, ~1, ~time+date, umf.cr, engine="R"))## Warning: K was not specified and was set to 103.##

## Call:

## gmultmix(lambdaformula = ~woody, phiformula = ~1, pformula = ~time +

## date, data = umf.cr, engine = "R")

##

## Abundance (log-scale):

## Estimate SE z P(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -0.0896 0.393 -0.228 0.81953

## woody 2.4294 0.591 4.107 0.00004

##

## Availability (logit-scale):

## Estimate SE z P(>|z|)

## -0.782 0.495 -1.58 0.114

##

## Detection (logit-scale):

## Estimate SE z P(>|z|)

## (Intercept) 2.1050 1.1139 1.890 0.058792

## time -0.0499 0.0142 -3.526 0.000422

## date -0.0285 0.1369 -0.208 0.835258

##

## AIC: 580.4508

## Number of sites: 50Results from this model are similar to those obtained using the subset of data, but the standard error for the woody estimate has decreased. If we back-transform the estimate of , we see that the probability of being available for detection is 0.31.

Another feature of gmultmix is that

can be modeled using either the Poisson or negative binomial

distribution. We might eventually add other options such as the

zero-inflated Poisson.